Medical mythologies exist in various forms and contexts. These can be understood as collective narratives, beliefs, or symbolic systems about health, illness, and healing that are socially and culturally constructed, rather than purely grounded in medical science. While “medical mythology” is not a standardized academic term, it is useful for analyzing how myths and cultural narratives shape people’s understanding of medicine and health.

Here are some examples and perspectives on medical mythologies:

1. Cultural and Historical Myths about Health

- Pre-modern explanations for disease: Many societies historically explained illness through mythological frameworks, such as punishment by gods, imbalance of humors, or possession by spirits.

- Modern equivalents: Even in contemporary societies, myths about the causes and cures of diseases (e.g., “colds are caused by being outside in the cold” or “cancer can be cured with a single natural remedy”) persist.

2. Medical Myths in Popular Culture

Media often perpetuates simplified or dramatized views of medical conditions. For example:

The idea that humans only use 10% of their brains.

The belief that cracking knuckles causes arthritis.

These myths influence public perception and, sometimes, healthcare choices.

3. Symbolic Healing and Mythology

- Anthropologists and sociologists, such as Claude Lévi-Strauss, have argued that myths in medicine often serve symbolic purposes, helping patients and communities make sense of suffering.

- Traditional healing practices, often rooted in mythology, can offer psychosocial benefits even without biomedical efficacy.

4. Medical Mythologies and Power

- Ernest Becker’s perspective: Anthropologist Ernst Becker suggests that myths around medicine can serve as existential buffers, helping individuals confront fears of mortality by placing faith in the “heroic” role of medicine or physicians.

Pierre Bourdieu’s perspective: Medical mythologies can also be seen as part of the symbolic capital of the medical profession, reinforcing doctors’ authority and the legitimacy of biomedicine.

5. Misinformation as Modern Mythology

- In the digital age, medical myths are propagated through misinformation and pseudoscience (e.g., vaccine myths, miracle cures). These narratives can develop into their own “medical mythologies,” driven by distrust of institutions or unmet medical needs.

6. Health and Wellness Mythologies

In wellness culture, myths often arise around diets, exercise, and supplements, such as:

- Detoxes can cleanse toxins from the body.

- Certain “superfoods” can cure diseases.

7. Pharmaceutical and Medical Industry Narratives

Myths created by marketing or the healthcare system itself (e.g., “This pill will solve all your problems” or “Doctors have all the answers”) reflect the interplay of economics, cultural expectations, and trust in medicine.

Critical Examination

Sociologists, anthropologists, and medical historians study these mythologies to understand their impact on health behavior, healthcare systems, and cultural attitudes toward illness. They can reveal tensions between traditional knowledge, biomedical science, and individual experiences of health and illness.

Medical Mythologies

Definition: Medical mythologies refer to the collective narratives, symbolic frameworks, or cultural stories that explain health, illness, and healing. They often transcend factual accuracy and are rooted in cultural, historical, or existential needs.

Features:

Symbolic and narrative-based: Mythologies create meaning around the unknown, such as why people get sick or how they are healed.

Cultural specificity: They vary widely across cultures and time periods (e.g., gods of healing in ancient Greece like Asclepius versus contemporary beliefs in “miracle cures”).

Emotional resonance: They address fears, hopes, and uncertainties, often acting as existential or moral guides.

Examples:

Beliefs about “miracle cures” or natural remedies.

The idea that certain diseases are divine punishment or karmic consequences.

Folk myths, like “cracking your knuckles causes arthritis.”

Medical Ideologies

Definition: Medical ideologies are systems of beliefs and values that underpin and justify the organization, practices, and knowledge of medical systems. They are more structured and systematic than mythologies, often reflecting power dynamics and cultural hegemony.

Features:

Institutional and systematic: Ideologies shape how healthcare systems are structured and how knowledge is produced and disseminated.

Often political or economic: They reflect power relationships and justify authority (e.g., the dominance of biomedicine over alternative medicine).

Normative influence: Ideologies prescribe “correct” ways of thinking about health and illness, often marginalizing other perspectives.

Examples:

Biomedicine as the dominant framework for understanding health in the West.

The medicalization of normal life processes (e.g., aging, childbirth, mental health).

Belief in technological progress as the solution to all health problems.

Key Differences

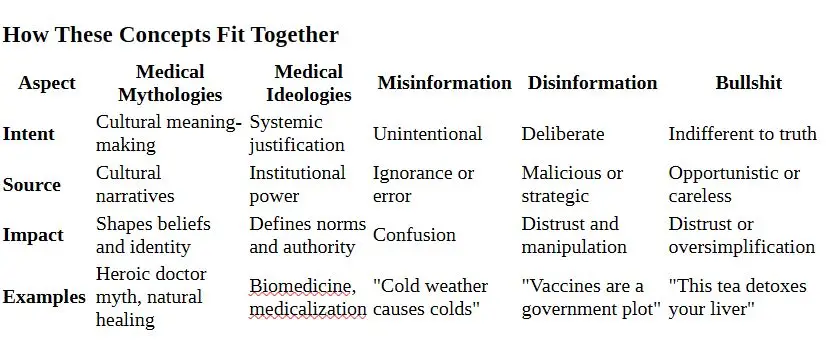

Aspect | Medical Mythologies | Medical Ideologies |

|---|---|---|

Nature | Symbolic, narrative, and often informal | Structured, systematic, and institutional |

Purpose | Explains meaning and provides comfort | Justifies authority and organizes practices |

Cultural Role | Addresses existential or cultural needs | Shapes systems and defines norms |

Focus | Stories and beliefs | Power dynamics, knowledge, and authority |

Examples | “Miracle cures,” “heroic doctors” | Biomedicine’s dominance, medicalization |

How They Interact

1. Overlap:

- Medical mythologies can reinforce medical ideologies. For example, the myth of the “heroic doctor” supports the ideology of medical paternalism.

Conversely, ideologies often draw on mythological narratives to justify their authority, such as the belief in technological progress as a “savior” in medicine.

Conflict:

Medical mythologies rooted in alternative or folk traditions can challenge dominant medical ideologies, such as beliefs in natural healing clashing with pharmaceutical reliance.

Sociological Analysis:

From an Ernest Becker perspective, medical mythologies might helppeople deal with existential anxieties about death, while medical ideologies enforce institutional control over those anxieties.

Pierre Bourdieu might view medical ideologies as forms of symbolic and cultural capital, while mythologies are tools for negotiating those systems of power.

1. Misinformation in Relation to Mythologies and Ideologies

Ideologies

Definition: Misinformation refers to false or inaccurate information shared without intent to deceive.

Connection to Mythologies:

Misinformation can stem from or reinforce medical mythologies. For example:

A belief like “Vitamin C cures colds” may originate from misinterpreted scientific studies or anecdotal evidence, evolving into a medical myth.

These myths are often perpetuated by well-meaning individuals who trust traditional or folk narratives.

Connection to Ideologies:

Misinformation can challenge or destabilize dominant medical ideologies (e.g., anti-vaccine misinformation undermining trust in biomedicine).

It can also arise from gaps in ideological communication—when medical institutions fail to clearly convey complex information to the public.

Disinformation in Relation to Mythologies and Ideologies

Definition: Disinformation is false information deliberately created to deceive.

Connection to Mythologies:

Disinformation often weaponizes medical mythologies to achieve specific goals. For instance:

Claims like “vaccines cause autism” draw on cultural fears and myths about scientific overreach or pharmaceutical greed.

It exploits emotional resonance, a hallmark of mythologies, to spread rapidly.

Connection to Ideologies:

Disinformation can be used to undermine medical ideologies, particularly biomedicine, by sowing distrust in institutions.

Alternatively, it can support ideologies that benefit from misinformation (e.g., pharmaceutical companies downplaying side effects to protect profits).

Examples:

Anti-vaccine campaigns funded by entities with ulterior motives.

Deliberate promotion of unproven “miracle cures” for profit.

3. Bullshit in Relation to Mythologies and Ideologies

Definition: Harry Frankfurt’s concept of bullshit refers to statements made without regard for truth, often to achieve personal or social gain rather than to deceive intentionally.

Connection to Mythologies:

Bullshit may exploit existing medical mythologies without caring whether they are true. For instance:

Wellness influencers promoting “detox teas” often neither verify nor care about their claims—they care about sales or visibility.

It amplifies mythologies by making them profitable or fashionable.

Connection to Ideologies:

Bullshit can reinforce or subvert medical ideologies, depending on its purpose:

Example: A hospital might emphasize the “heroic doctor” narrative in marketing campaigns, even if the truth is that healthcare is a collaborative effort.

In alternative medicine, bullshit often undermines the ideology of biomedicine by appealing to distrust and offering vague, unsupported solutions.

Examples:

Unscientific claims like “this crystal balances your energy fields” by individuals who neither know nor care about the scientific basis of their statements.

Sociological Implications

1.Reinforcement or Disruption of Power:

Disinformation and bullshit often disrupt dominant medical ideologies, but they also create their own pseudo-ideologies (e.g., the anti-vaccine movement’s “natural immunity” narrative).

Misinformation can unintentionally reinforce medical mythologies, like home remedies being seen as “better than pharmaceuticals.”

Cultural Capital and Symbolic Authority:

Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic capital applies here: misinformation and bullshit can erode trust in institutional symbolic capital, like that of doctors or medical researchers, by elevating alternative sources of “truth.”

Existential Anxiety and Becker’s Framework:

Disinformation and bullshit may appeal to existential fears about mortality by offering comforting, albeit false, solutions or explanations.

Mythologies remain effective because they address underlying emotional and existential needs.